This week comprises three presentations on distinct but related topics. The first to discuss is Bonnie Stewart’s presentation on Datafication.

Sometimes a good chorister enjoys being preached to. Stewart’s talk on datafication outlines many of the ways that the reduction of lives into data which can be analyzed, commodified, and sold is used by the powerful to exert their control. A lot of these ideas are familiar to me, and the lens Stewart takes towards the social influences they cover is quite similar to that which I try to apply in my own understanding of current affairs.

The issue of the reductivity of data is particularly impactful in EdTech, where a primary purpose of a lot of educational technology is improved ability to surveil the progress and activities of students, which can grant a useful level of detail or play into a “teach to the test” mindset around maximizing educational practice towards whatever benchmark can be easily measured. It should not go unsaid that systems are built with purpose, and the benchmark a system measures can be designed around pushing the interests of the unelected heads of large companies whose interests may or may not align with societal well-being.

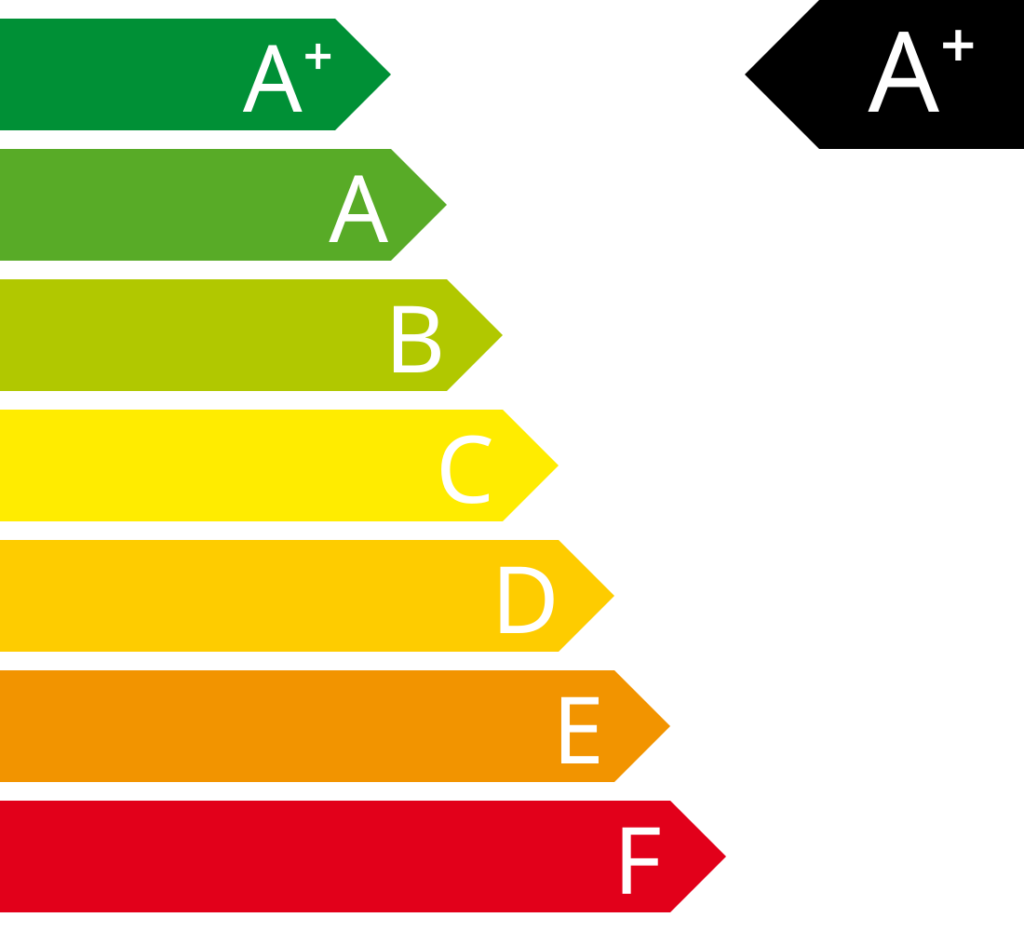

A lot of conversation around datafication of educational practice calls to mind Goodharts Law: When a measure becomes a target, it ceases to be a good measure. Having one number be a target allows for enormous exploitation to make that number go up, which can be divorced from genuine improvements. The most famous example is the Cobra Effect, wherein the British Raj attempted to reduce cobra populations in Dehli by putting a bounty on cobras, resulting in cobra breeding farms to harvest more snake corpses, resulting in a rise in cobra populations. This incident likely didn’t actually happen, I can find no reliable source for it and the bit of this article above the paywall seems to suggest historians dispute it, but it’s demonstrative regardless. Musk and his DOGE agency seem to be doing Goodhart’s law on purpose, or at least with reckless negligence, aiming to cut the biggest amount of government spending without much regard for how much damage they do to basically everything. Reduction of people to data essentially turns everything into a perverse incentive; humanity and societies can perhaps be understood more thoroughly with detailed statistics, but to base policy and worldview on numbers exclusively isn’t rational, it’s just inhumane.

Wency Lum offered a basic overview of cybersecurity threats and some best practices to protect oneself from attacks. A primary focus was identifying phishing scam emails, which, when one is diligent, is not exceptionally difficult. UVic often sends it’s own phishing emails to train people to spot them by linking to a “you fell for it” page, which definitely made the threat of phishing more tangible when I clicked one of the links in my first year. The emails seem to have had an opposite effect on a coworker in Reslife, who told me the other day that she saw one, thought “I bet thats one of those phishing emails”, and clicked the link and was satisfied when she was right and it went to the UVic phishing warning page. This really highlights a point that Lum brings up: cybersecurity is a collective effort reliant as much on people as the systems you build for them.

Charlie Watson’s talk on accessibility outlines various conditions requiring accommodation and many existing tools that currently aim to fulfill that purpose. Watson also lays out various techniques to ensure digital design is accessible to everyday users and the tools that facilitate digital engagement.

A core framework I picked up on was a chain of design intentionality that is required for disabled people to function in society; for people to participate, they need technology built for their needs, and for that technology to function, infrastructure must be built to facilitate it. A person needs a mobility scooter to move, a mobility scooter needs a ramp to get up an incline; infrastructure is built for tools which are built for people. In order to pursue digital accessibility, you must understand the internet as infrastructure, where, just as a mobility scooter is useless in a building full of stairs, a screen reader is impaired in it’s function when it engages design that doesn’t use heading systems properly, relies on coloured text for information conveyance, or uses images of text instead of usual script. It’s always a good thing to affirm that accessibility isn’t a problem that can be solved externally; it must be built into the core design of our societal infrastructure lest disabled people be left behind.

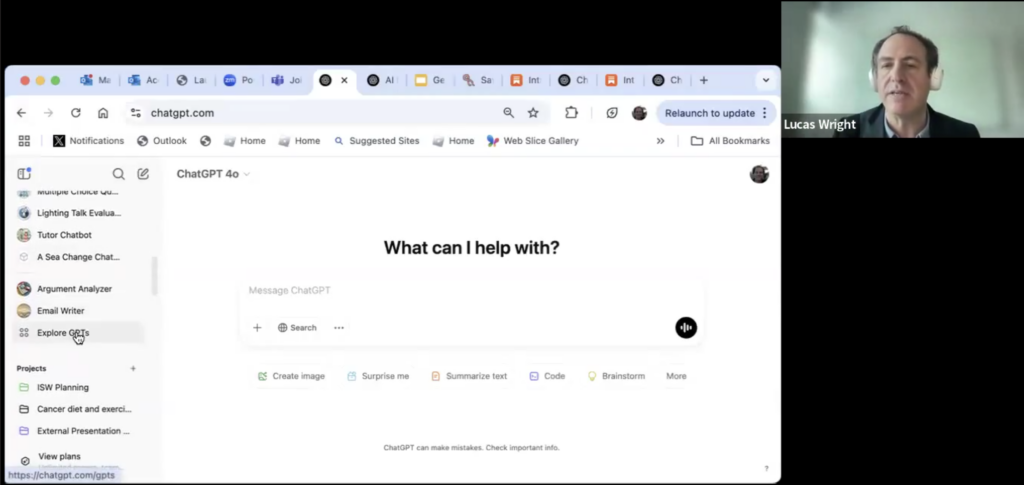

![screenshot of Lucas Wright's email responder. Lucas types "Yes I have dont worrry", the chat bot responds with "Here's a concise and professional response:

Subject: Re: Power Bill

Dear [Sender's Name],

Yes, I have checked the power bill today - no need to worry"](https://edci136--xmarican.opened.ca/wp-content/uploads/sites/9158/2025/03/image-4-1024x549.png)