This week’s materials focused primarily on issues surrounding eroding privacy in the digital realm and the effect of this erosion on our lives, along with a brief interview with Nodin Cutfeet on their Waniskaw Foundation for Indigenous digital literacy.

A lecture given by Ian Linkletter this week had a large focus on opposing AI proctoring software, digital tools designed to algorithmically analyze data from cameras and browser monitering during exams to prevent students from cheating. This sort of use of AI can seem benign, but it’s representative of a deep incompetency in the use of many modern AI tools; an ignorance of their need for supervision.

The below video by Physicist Angela Collier outlines some flaws and false narratives surrounding AI technology with a focus on it’s place in science. The section “What AI is not” focuses on why experts are necessary in the process of using these tools. One example offered is the use of machine learning to diagnose Tuberculosis in samples given to an algorithm to analyze. The algorithm was built well enough to be able to diagnose Tuberculosis more accurately than doctors overall, but it was still important to probe the responses it gave to find out how it was coming to the conclusions at which it arrived. Through AB testing, it was found that the algorithm was measuring the date that the pictures were taken and weighing older pictures to be more likely to contain Tuberculosis in the samples than newer ones. Because older machines were used in places with more Tuberculosis and thus more positives, the algorithm didn’t simply notice the trend, but incorporated it into it’s assessment as though it were a causal factor. This is because machine learning is, as Collier frequently emphasizes, not intelligent, and has no way of understanding causality, so even as this algorithm became more effective than humans at diagnosing Tuberculosis samples, it was still including nonsensical data based on an irrelevant bias in it’s analyses which could potentially cause serious harm.

AI proctoring tools fly in the face of these concerns. These tools reproduce biases and confer important judgements without proper supervision and often without a clear idea of how they are coming to their conclusions. On a basic level, they should not be trusted to function without the kind of heavily involved supervision that would make their usage redundant. Even with greater supervision, what camera systems flag are simply reconstructions of biases we have about how students should look or act. The prominence of facial recognition failing to find black faces is relevant here, as well as the list of abnormalities that Linkletter claims that AI proctoring tools highlight, including deviations from the norm in head movement, eye movement, keystrokes, and clicking. This seems like a machine perfectly constructed to bring scrutiny to neurodivergent or differently abled students, and it is no surprise at all that Linkletter was able to cite a Dutch study that showed that the effectiveness of a particular proctoring software was no more than that of a placebo. The idea that people who move in odd ways are more likely to be cheating, when you think about it for more than a moment, is absolute nonsense. It’s the academic integrity equivalent to the body language experts in British tabloids claiming that Meghan Markle is a sea witch because she tucked her hair behind her ear too many times.

In his podcast on digital surveillance, Chris Gilliard focuses on the increasing prominence of surveillance tools acceptance in our lives, including cctv cameras in businesses that feed directly into police stations, doorbell security cameras surveilling neighbourhoods, and consumer tech products offering conveniences while collecting data to sell.

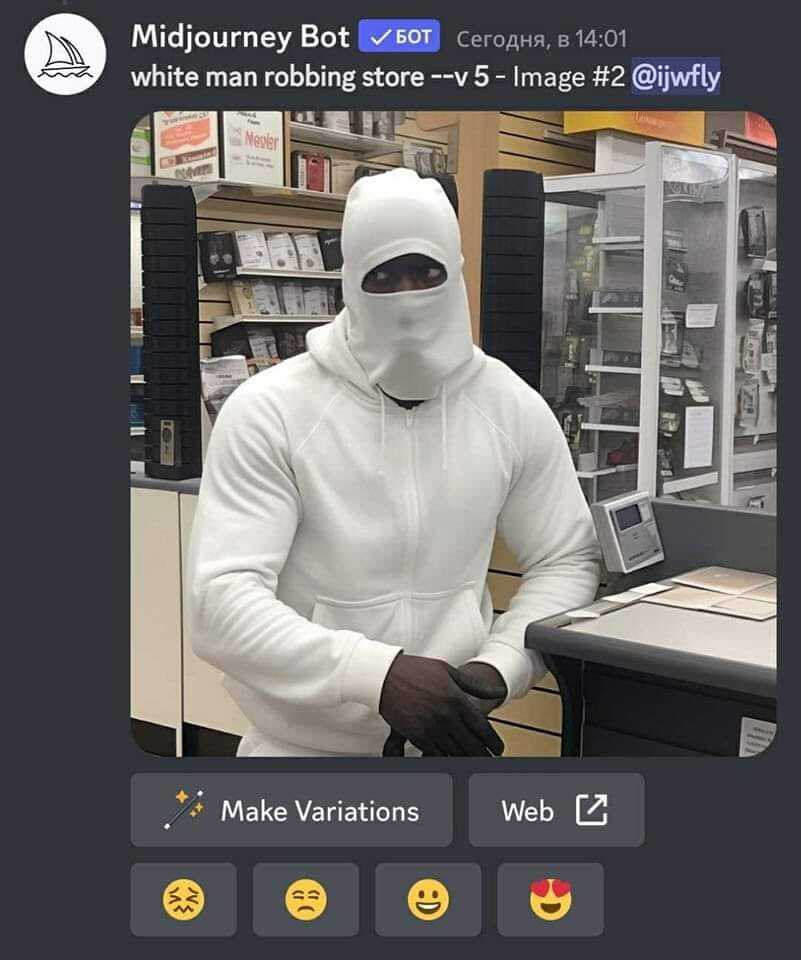

A big theme of the podcast was who surveillance is aimed at. Gilliard mentions how wage theft takes far more money out of the pockets of American citizens than shoplifting takes from corporations, but we don’t see cops patrolling corporate offices. Surveillance technology is based in bias. Linkletter also mentioned how algorithmic tools play on our assumptions that computers are less irrational than humans, but the data they use is always collected by squishy-brained humans with biases and within systems built on them. If people of colour are more likely to see their behaviour criminalized, more crimes will be reported in a racialized area, and if the response is an increase in surveillance, the fact that more eyes are on the area will mean that more crimes will be reported without any need for crime in the area to increase, or necessarily be more prominent than in another, less surveilled area. Data is collected through bias, so data analysis will always hold on to the same biases.

On the subject of consumer technology, Gilliard raises concerns over how many products are accepted as items of luxury surveillance, tracking data to offer a consumer convenience in exchange for privacy. Fitness watches, for example, track your heartrate, steps, and location, which I presume is very helpful for people who use them, but this amount of personal info being in the hands of large corporations aiming to squeeze as much value out of consumers as possible is disquieting at the very least, especially given the precedent Gilliard mentions of these companies readily sharing their data with law enforcement. You have nothing to hide only until you disagree with the state on what behaviour is acceptible. As we are quickly seeing in the United States, this is not as unlikely as we might think.

Nodin Cutfeet’s Waniskaw foundation seems to be an excellent example of community oriented activism. The organization aims to improve digital literacy in underserved indigenous communities by utilizing programs, hardware and community engagement that fall in line with the priorities and capacity for engagement in reserve communities. Cutfeet mentions that in many indigenous reserve households, the closest devices to a computer are xboxes or other consoles with a web browser installed on them, and getting grants that would allow them to send compatible keyboards to these households to facilitate digital engagement on the devices they already have is a potential goal for their organization. The understanding represented by this idea demonstrates a genuine connection to the community being served that I see as a positive example for effective organizing.

I enjoyed Cutfeet’s mention of differences in motivation between mainstream and indigenous engagement in coding education, how indigenous students are less susceptible to Zuckerburg admiration and promises of wealth and control. Rather than presenting them as being too high-minded or principaled for that sort of thing, Cutfeet frames this lack of effectiveness as indigenous youth being more interested in seeming smart in front of their friends and community than being corporate big-shots. It’s not so high a bar to expect an indigenous person to not engage in noble savage stereotypes, treating their place outside of mainstream expectations as an untainted purity from our materialism, but the fact that it isn’t a worry underscores the benefit of the awareness and connection Cutfeet has in this community.