This fireside chat with Lucas Wright makes me concerned for the state of our minds going forward. The offloading of cognitive tasks to bland forest-burning bots regurgitating the mean average of all of the questionably legally obtained data they have is so not inspiring or exciting to me; the most positive feeling it instills in me is a sense of resignation to the continuing decline of our ability or motivation to think for ourselves.

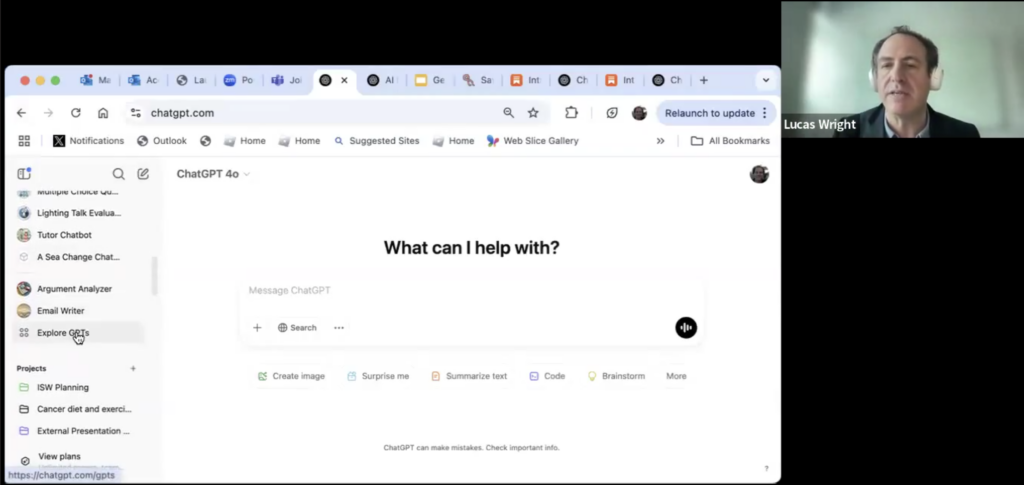

Plato was known to be opposed to writing. He commented on it’s invention in Phaedrus, claiming that students “will cease to exercise memory because they rely on that which is written, calling things to remembrance no longer from within themselves, but by means of external marks.” I used to find this fact reassuring; it shows that people have been sounding alarms about how new technology will make us stupider for thousands of years, yet humanity marches on. The rise of generative AI has changed my opinion on this fact, and it now only fills me with dread. In the chat, Wright demonstrates a process of creating a presentation on evaluating judgements during which he tells the bot to collect sources, has the bot summarize them, uses a bot to create diagrams out of those sumarries to use in a presentation, and then gets the bot to create a learning activity relating to the information. The act of knowledge communication here is being treated as a discardable obstacle, and the cognitive ability to research, understand writing, and communicate one’s ideas is being discarded with it. Just as Plato could never have done anything to preserve our memories and stop us from relying on paper, we in modern times will not be able to do anything to stop humanity from giving up on finding, understanding, and communicating information without offloading the task to water-polluting data skimmers brought to you by the Alphabet Corporation.

Wright mentions a move from a “search and create” model to a “generate and evaluate” model. I believe this shift is one that turns knowledge communication into an empty task. Ask Carl Sagan, David Attinborough, or Bill Nye what they think about removing “create” from the process of communication. These people demonstrate that knowledge is granted power, influence, and accessibility through the way it is communicated, and they show the difference that is made when it is communicated passionately and creatively. Even on the smaller scale of presentations, reports, or blogs, knowledge has meaning because it is important to human beings, and we should be purposeful in what and how we say things lest information become meaningless to us. Every word in, for example, a scientific paper, has a purpose. These papers are long because they contain nuance, detail, and often the personality and opinions of writers. AI summaries exist to remove all of these things. They create easily consumable bullet points of only what they “think” is essential, and in the process deprive the user the experience of judging and interpreting information for themselves. Even reports and papers are (ideally) created with intent by incredibly dedicated, knowledgable people who communicate specific facts in a specific manner to underscore their importance, and relying on quick AI summaries bulldozes this work in a depressingly disprespectful fashion. Evaluation of AI summaries is not enough. You either lose the voice, intention, and nuance of the authors, or check the articles thoroughly enough to ensure nothing was missed, in which case the AI summary is nothing but a redundancy.

On the subject of redundencies, Wright mentions his AI emailing tool and talks about how AI will give way to new forms of communication. This is because he uses a bot to change “no worrries” to “Dear ____, You don’t need to worry” and he imagines a second person who will, unwilling to read the email themselves, use a bot to summarize it back down to “no worries.” The only inefficiency here worth addressing is AI itself. We’re so afraid of being curt (and so offended that someone might be curt towards us) that we have built a gazillion dollar atmosphere hole-punching machine and used it to add and remove formalities.

![screenshot of Lucas Wright's email responder. Lucas types "Yes I have dont worrry", the chat bot responds with "Here's a concise and professional response:

Subject: Re: Power Bill

Dear [Sender's Name],

Yes, I have checked the power bill today - no need to worry"](https://edci136--xmarican.opened.ca/wp-content/uploads/sites/9158/2025/03/image-4-1024x549.png)

Wright is later asked about how he copes with the environmental damage done by these generative models. He says that it is unfair that consumers have their feet held to the fire when the corporations are the ones who should be held responsible. This often valid criticism is being used here as a thought terminating cliché to absolve Wright of any personal responsibility. “Corporations are damaging the planet, not individuals, so I won’t stop throwing my used car batteries into the ocean, thank you very much.” In this blog, I have tried to keep much of my criticism more broadly focused to the field that Wright describes rather than towards him specifically, but in this case I feel some individual commentary is warranted. On a daily basis he is using and endorsing these tools which have not yet become so ubiquitous as to be required, so he is part of the problem of how their proliferation opposes sustainability, and the shallowness of his deflection of this fact verges on the parodic.

When we invent technologies that carry a function, it replaces that function in us. The GPS has largely replaced our inner compass, constant calculator access has made us worse at mental math, and paper has made us worse memorizers. I do not care how practical generative AI can be in replacing our ability to research, process, and communicate information; these abilities are ones we should never let humanity leave behind. We must at some point draw a line at what we can’t be bothered to do on our own, and for me, that line is far earlier than giving up on reading and writing anything longer than two sentences.